Unicorns Vs. The Titans: The biggest players in the biggest industries are now seriously executing on technology-driven innovation initiatives. Here’s how.

An Indicative Research Report

Key Findings

We analyzed the Fortune 500 to understand how large incumbents in some of the biggest industries are executing on technology-driven innovation initiatives.

We focused on a subset of 70 companies in 3 verticals that are cornerstones of the economy – Financial Services, General Retail (e.g. including broad-line retailers and specialty retailers), and Automotive Retail (e.g. the largest automotive dealer networks).

These companies:

- Predominantly have business-to-consumer business models that generate significant amounts of Behavioral Data

- Face a significant amount of competition from startups in their space

Focusing on these 2 criteria help us focus on examining companies that are likely to both have significant data assets (and thus innovation leverage) as well as face robust competition from new players.

We then analyzed these companies across a variety of metrics to understand how they both develop capabilities and execute on innovation initiatives.

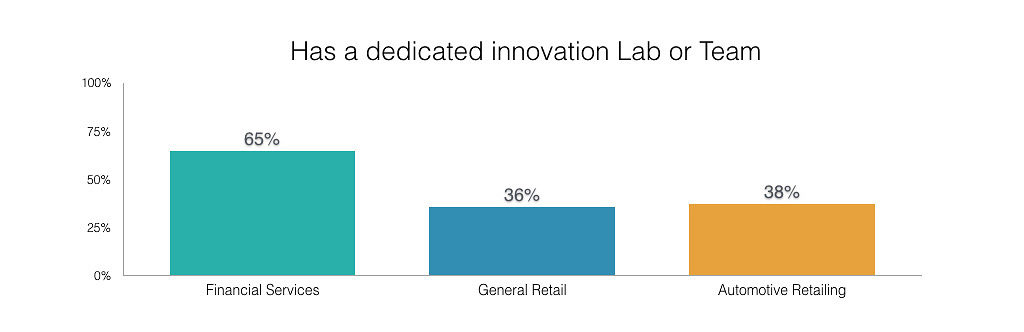

Team

65% of Financial Services companies have a dedicated innovation lab, division, or specific new product innovation groups, where only 38% of Automotive Retail and 36% of General Retail companies do.

Output

Those with dedicated labs or innovation teams are more than twice as likely to have launched at least one major digital innovation within the last 3 years.

Industry

Financial Services companies, in general, are much more likely to shipping more digital product than retailers. It looks like banks can fully cast aside their reputation for being old and stodgy vis a vis the retail sector of the economy.

Executive Sponsorship

Of those with labs or teams with direct C-level sponsorship, 100% have shipped significant digital products, indicating a strong C-level buy-in does help get more major initiatives out the door.

Background

It’s not just the startup world, that speaks ubiquitously of “unicorns,” used to describe billion-dollar startups or the public declarations from prominent venture capitalists like Marc Andreesen that “software is eating the world” that foresees the potential digital disruption in every corner of the economy. In fact, with old industry stalwarts like Jeff Immelt, the CEO of GE, declaring that “every company is a software company,” the public perception is often that for many existing titans of industry, their remaining days at the top are numbered.

Even in banking, the most traditional of industries, Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase, warned last year in his annual letter to shareholders that “Silicon Valley is coming”, and that “there are hundreds of startups with a lot of brains and money working on various alternatives to traditional banking.”

While many disruptions are often unforeseen, and many Silicon Valley startups are targeting weak incumbents on a business model level (e.g. Uber vs the tens of thousands of small cab companies all over the world), many of the largest industry incumbents are not as disadvantaged. In fact, many that have direct relationships with customers have enormous advantages over startups in a critical key area: they have massive amounts of “Behavioral Data”, e.g. all the data exhaust that is generated from each customer interaction, whether it’s a click on a website, a purchase in a retail store, or a call taken in a call center.

Companies with all this data potentially have a built-in advantage in crunching data from their existing customers to identify new products and new markets ahead of Silicon Valley. This is no secret to enterprise CIOs – year after year Gartner and other research firms highlight that the #1 priority for CIO investment is analytics and data capabilities.

However, companies have a variety of different models of innovation available to them to build digital products.

On one end, there is the “bi-modal model” where companies create specialized, isolated teams separate from the existing business, often for “big-bang” approaches.

On the other, there is a fully “integrated” model where the expectation is that the existing teams in different areas of the business already in place are responsible for innovation.

There has been much discussion (and little agreement) on whether the “bi-modal” approach to enterprise innovation is a recipe for success or disaster.

And some firms have even taken a completely different tack – developing an “open innovation” approach where they seek to primarily partner and nurture outside startups, vs build their new technology. This is based on the belief (or acquiescence) that innovation is going to happen outside their organization, and the best use of the company’s resources are in helping fund, purchase, partner on, or eventually acquire innovative technology from startups. Barclays Bank in the UK is a prominent example, who has even partnered with Techstars to build multiple co-branded startup incubators.

Given the multitude of approaches and the stakes of the battle for the American and the world economy, it’s worth taking a comprehensive look at how the biggest Fortune 500 companies, who are sitting on enormous amounts of data and budgets, are approaching innovation.

We decided to tackle this with numbers and do a quantitative and qualitative analysis of what industry incumbents are doing with access to large amounts of behavioral data are actually doing in two dimensions:

- How they are building the teams and capabilities to innovate

- What approach to shipping product are they taking – e.g. if they are taking incremental approaches or shipping major new products.

We focused this analysis to the 70 companies in the Fortune 500 2015 rankings in 3 key industries that have access to enormous amounts of behavioral data.

More details on our analysis methodology are in Appendix A, and the full list of companies analyzed is in Appendix B.

Findings:

We looked at 5 key factors when evaluating companies:

- Whether or not they had built separate innovation, labs, or new product development teams

- Whether or not these teams were staffed with a complete team to be able to deliver a complete digital product (e.g. if they have developers, product managers, designers, and data scientists/data specialists all working together full time vs a more distributed approach)

- Whether or not these teams had direct C-level representation (e.g. is this team have a C-level executive or do they report into a C-level executive)

- Whether or not they had shipped at least one major digital product initiative within the last 3 years that was aimed at entering a new market or product category (vs say just launching a mobile app that is a complement to an existing website experience or adding on existing digital features)

- Whether or not they had shipped at least two or more major digital product initiatives within the last 3 years that was aimed at entering a new market or product category

Industry Breakdown:

Across three main industries we analyzed (Financial services, General Retail, and Automotive Retail), there is a significant difference in their approach to innovation:

65% of Financial Services companies have a dedicated innovation lab or labs, where only 38% of Automotive Retail and 36% of General Retail companies do.

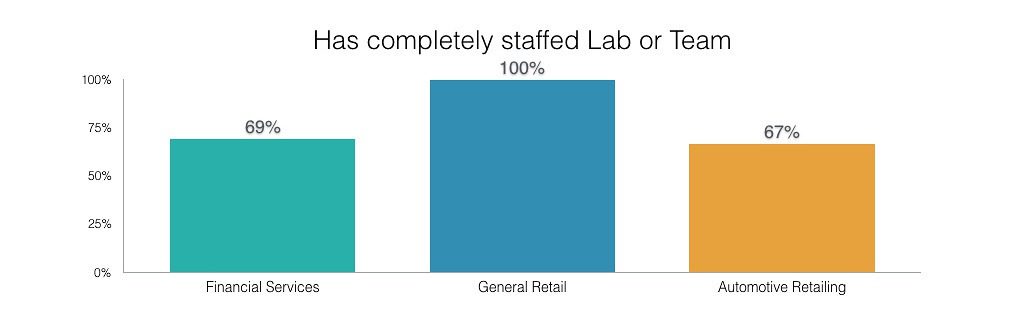

Team Comparison:

100% of the General Retail innovation groups have a complete team of developers, product managers, designers, and data scientists to ship complete digital products, while only ⅔ of the Automotive Retail companies and ~70% of Financial Services lab teams are set up the same.

The other innovation teams are predominantly strategy focused, acting as a specific consulting arm, and dependent on other parts of the organization to implement innovative concepts.

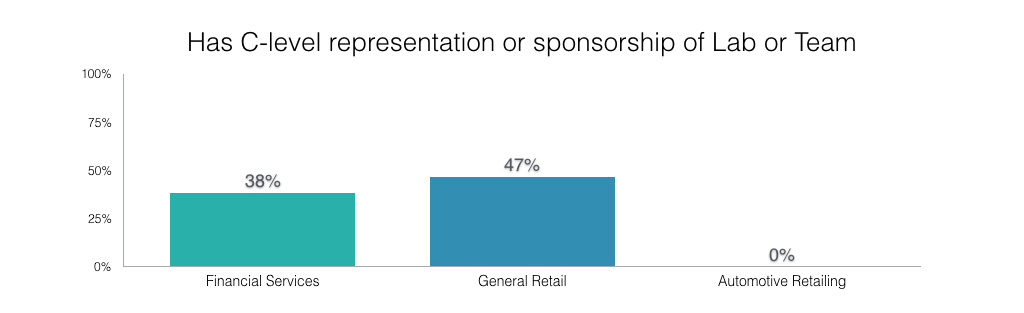

Leadership Comparison:

For those companies that do have actual dedicated teams, only 39% of Financial Services and 47% of the retailers have a C-level representative where innovation is a primary component of their portfolio (e.g. a Chief Innovation Officer), and none of the Automotive Retail companies do.

The other teams report into a variety of other areas, most commonly into or a level below the CIO, and less frequently the CMO or COO.

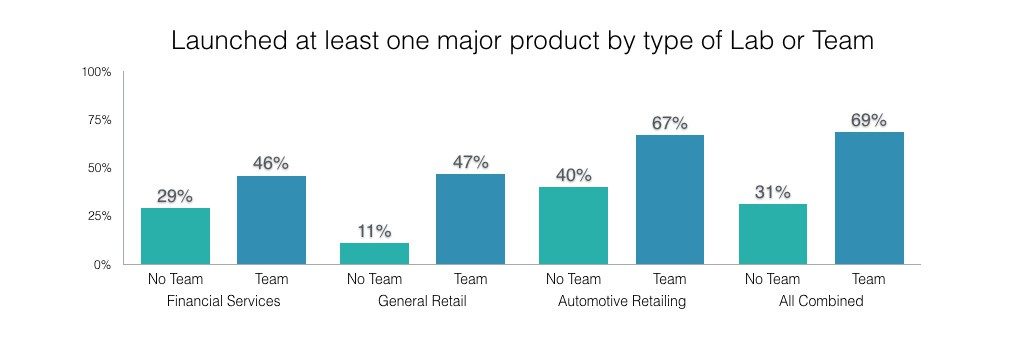

Digital Product Launch:

When it comes to launching new digital products, it’s clear that having a dedicated team results in a higher volume of product launches.

In fact, those with dedicated teams labs are more than 2x likely to have launched at least one major digital innovation in the last 3 years.

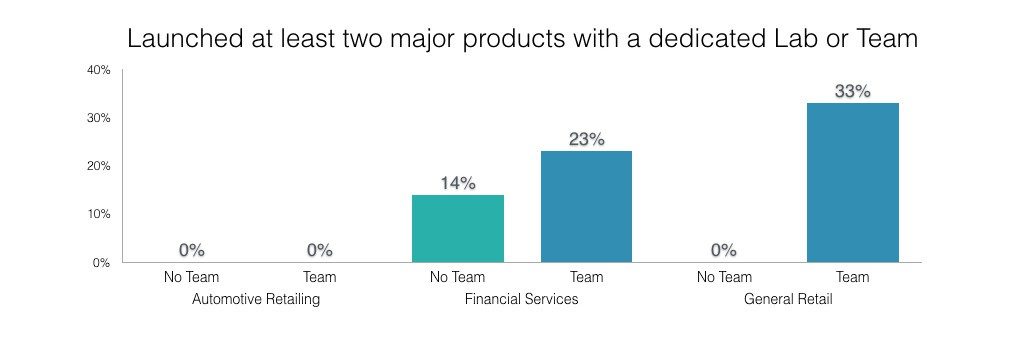

Interestingly, no company in Automotive Retail launched at least 2 initiatives, trailing the volume of product release of both General Retail and Financial Services.

Overall Financial Services firms are more likely to launch 2 or more (at 23% vs 14% of the other 2 industries, putting rest to the stereotype of “stodgy” banks.)

Interestingly, Financial Services companies almost more likely to launch major product initiatives without a dedicated innovation team as well (65% have launched 2 or more major digital products without dedicated labs, while only 38% in both general retail and automotive retail.)

Another interesting note – No General Retail company launched 2 or more initiatives without a lab, unlike Financial Services, indicating that more dispersed innovation models are more likely to be present in banks vs retailers.

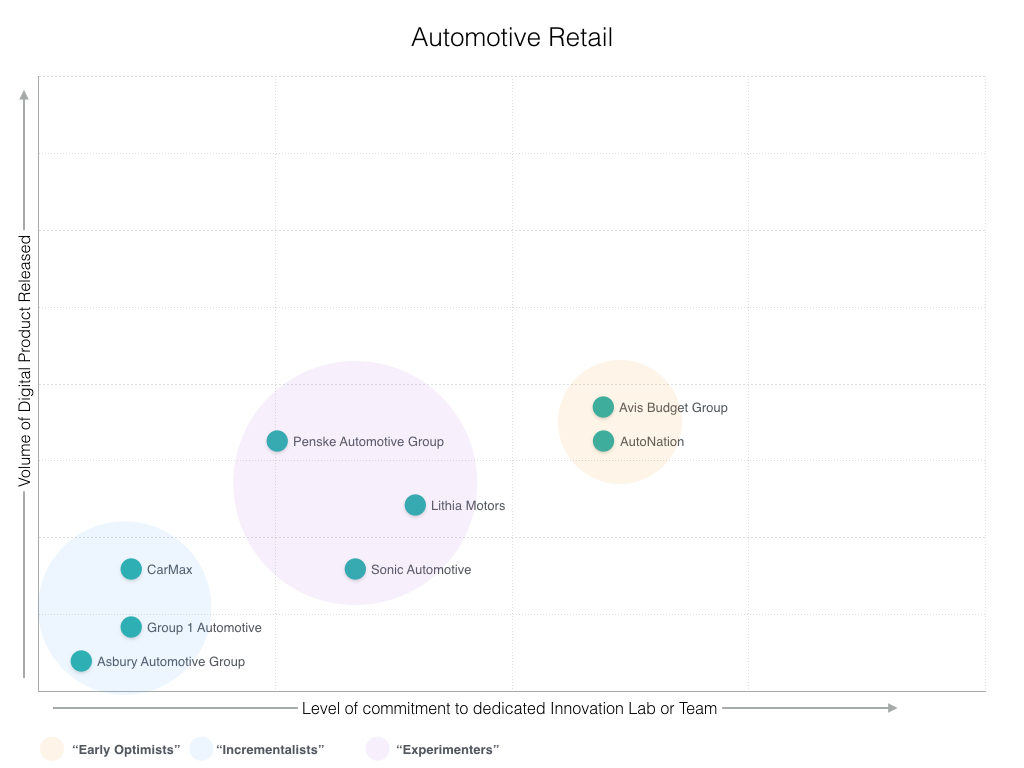

There Are 6 Different Approaches To Innovation, And They Vary By Industry:

Description of approaches:

We identified 6 categories of how these companies approach innovation:

- “Incrementalists”

These organizations have not yet built or decided to eschew dedicated innovation approaches, instead of focusing on incremental innovation dispersed across the enterprise. This results in less “big” product launches and market entry, but more focus on internal improvements. This can be indicative of a company who isn’t bought into a bigger digital transformation, or a company that’s been burned with an innovative approach that didn’t pay off.

For example, Bank of America’s CIO, Cathy Bessant is firmly in the camp of incremental innovation spread across the enterprise, believing that “it’s more powerful to capture innovation from ten thousand people than to put 10 people in a lab,” and “…[p]artnering is important.” Additionally Bank of America has a “team dedicated to looking at emerging technologies and new players,” and collaborates with startups via an “annual technology summit.” However, this wasn’t always the case.

Nordstrom is another example of a company who more recently pulled back from the dedicated team approach, reassigning its team to be embedded into different parts of the business. While there was certainly a rapid, iterative approach to experimentation, the company felt like these smaller, isolated experiments weren’t having the desired impact.

- “Experimenters”

These organizations have started dipping a toe into digital innovation on an ad-hoc basis, without a dedicated innovation lab or team. As opposed to a broad innovation investment and an executive sponsor throwing their weight behind, these companies have typically attempted to marshall their organizational to tackle once-off, large strategic projects.

For example, in the face of significant competition from startup “Robo Advisors” like Betterment and Wealthfront, Charles Schwab built their own “Intelligent Portfolio” platform. They’ve put some heavy marketing muscle on it as well, and aren’t afraid to fight back at some of the startups that have challenged them.

- “Believers”

These are companies that have built dedicated innovation teams and conducting regular experiments, but don’t have C-level executive but haven’t yet started launching large initiatives. Some of these companies may not be looking to drive big initiatives, but rather see where ad-hoc experimentation takes them and generate some PR in the process.

Several companies, in particular retailers, have developed this approach via acquisition – essentially acquiring a company with a complete technology team and tasking them to continue to experiment and build out a new product, often in a satellite location.

An example of this approach is Lowe’s, which built an innovation program by acquiring Black Locus in 2012. The team is focused on key areas that they worked on prior to the acquisition like predictive pricing analytics, operating as a group of dedicated experts on smaller projects throughout the organization.

Additionally, companies that have only recently launched a lab initiative fall into this category. An example of this is CVS, which launched a new digital lab overseen by the Chief Digital Officer in June of 2015, and has some early incremental wins like an in-store beacon platform integration into their mobile apps.

- “SEAL Teams”

These are companies that have built dedicated innovation teams but don’t have the air cover of a direct C-level sponsor, and yet are still successfully shipping major new product.

This is an approach that is most often seen in companies with strong technical DNA, large cash piles, or with the widespread support of big initiatives at different levels of the organization.

An example of this is Walmart Labs, originally built by the $300m acquisition of Kosmix in 2012. While the head of Walmart Labs and former Kosmix CEO reports into the Neil Ashe, the president of Walmart’s E-commerce division, the primary focus of Ashe’s portfolio is playing catchup to Amazon in core product, and most of the Labs team is focused on small pilots like Walmart Pickup-Grocery (a curbside grocery pickup kiosk) or internally focused on projects like real-time pricing.

Most importantly, the majority of the Kosmix team has stayed at Walmart Labs, creating a significant advantage in continuity and delivery effort.

- “Early Optimists”

These are companies that have full dedicated teams, some executive sponsorship, and some early wins under the belt but are not yet shipping major digital products regularly. Many are similar to the Experimenters in that they have started with a major bet, but

A good example of this is Autonation, who not only spent $100m building an e-commerce operation that risks cannibalizing part of its core business but is doubling down on its technology investment and continuing to build out digital technology with that team.

- “Dedicated innovators”

These are companies that are fully bought in – they have built full innovation teams, have a direct C-level sponsor, are successfully shipping new product regularly.

This is typically found at an organization where the CEO has digital innovation or transformation as one his or her top priorities and has empowered the rest of the organization to both invest heavily.

An example of this is Target, with multiple labs and a C-level sponsor, that is both building new independent digital products as well as building digital in-store experiences.

Conclusions:

While it’s clear that some of the companies in the most traditional sectors of the economy are embracing digital innovation, it’s still early in the transition to point to a single successful innovation approach.

There is certainly clustering happening at each end of the spectrum – most companies are either decidedly averse to building dedicated innovation teams, or going all-in. And just like technology startups themselves, many big bets are starting to see results, though there are some big-name casualties along the way.

For other large enterprises that are thinking about investing in innovation, a couple of recommendations can be gleaned from this analysis:

- The most prolific innovation teams have a direct C-level sponsor – if an exec has to ensure they deliver as a primary responsibility, they mostly end up delivering.

- Teams that deliver are fully staffed with developers, designers, and product managers – a strategy-only approach of “Powerpoint jockeys” won’t result in output.

- Delivery of internal improvement projects that show real business value can provide air cover for both “bigger bang” strategic initiatives as well as more exploratory, pure research type of experiments.

- Launching a lab via acquisition is a viable strategy, but it needs to be the right team that wants to and has the right incentives to stay intact.

———————————————————–

Appendix A:

To build this analysis, we did the following:

- We looked at every company in the Fortune 500 to determine which companies generate significant direct behavioral data from interactions with customers either in a Business-to-Business or Business-to-Consumer fashion – this narrowed the list to 158 companies

- We furthered narrowed our analysis to only companies who sell primarily to consumers in a B2C model in a direct fashion, as they are the ones sitting on the largest amount of behavioral data. E.g. this includes companies like Walmart that interact with consumers directly either in-store or online, and doesn’t include say, energy companies like Exxon.

- We further narrowed our analysis set to a subset of industries that have seen the most amount of startup activity in their space and where there is an opportunity for primarily digital innovation. This narrowed our industry focus to 3 key industries: Automotive Retailing, Financial Services, and General Retail, resulting in a total analysis set of 70 companies. Note that Insurance companies are excluded from Financial Services.

- We analyzed all 70 companies across two dimensions:

- Capabilities (e.g. whether they had built the teams and given the strategic focus to innovation). This is a weighting based on

- The presence of dedicated new labs, innovation, or new product organizations

- The right support given to those teams to be able to actually build products (e.g. do they have dedicated product managers, developers, designers and data scientists)

- The right executive buy-in (e.g. does this team have a C-level executive or do they report into a C-level exec)

- Execution (e.g. whether they had actually built and launched a new product). This is a weighting based on:

- Having two or more significant product or market entry initiatives in the last three years

- Whether the organization was supporting them strongly

- Whether there was a transition into a full-time dedicated team running the initiative post-launch

- Capabilities (e.g. whether they had built the teams and given the strategic focus to innovation). This is a weighting based on

Appendix B:

Included Company list:

- AutoNation

- Penske Automotive Group

- CarMax

- Group 1 Automotive

- Sonic Automotive

- Avis Budget Group

- Asbury Automotive Group

- Lithia Motors

- Charles Schwab

- Jones Financial

- Western Union

- Ameriprise Financial

- Regions Financial

- Fifth Third Bancorp

- SunTrust Banks

- Discover Financial Services

- Ally Financial

- BB&T Corp.

- State Street Corp.

- PNC Financial Services Group

- Bank of New York Mellon Corp.

- U.S. Bancorp

- Capital One Financial

- American Express

- Wells Fargo

- Citigroup

- Bank of America Corp.

- JP Morgan Chase

- Tractor Supply

- Barnes & Noble

- Pantry

- Dick’s Sporting Goods

- PetSmart

- Casey’s General Stores

- O’Reilly Automotive

- TravelCenters of America

- Dollar Tree

- GameStop

- AutoZone

- Advance Auto Parts

- CST Brands

- Bed Bath & Beyond

- Toys “R” Us

- Murphy USA

- Office Depot

- Staples

- Best Buy

- Lowe’s

- Home Depot

- Costco

- TJX

- Amazon.com

- Dillard’s

- Family Dollar Stores

- J.C. Penney

- Nordstrom

- Dollar General

- Kohl’s

- Macy’s

- Sears Holdings

- Target

- Walmart

- Whole Foods Market

- Supervalu

- Rite Aid

- Publix Super Markets

- Safeway

- Walgreens

- Kroger

- CVS Health